The True Story of the Telephone

I grew up in Highland Park, Illinois, just down the street from where the telephone was invented. I now live in Cambridge, Massachusetts, just down the street from where it was stolen. Seth Shulman’s recent book The Telephone Gambit lays out the clearest case yet of how it all happened. Here’s the summary:

Alexander Graham Bell (or Aleck Bell, as he was then called) was the son of Alexander Melville Bell, the inventor of a system of phonic notation called Visible Speech. The elder Bell would use Aleck as an assistant in his demonstrations: After sending Aleck to wait in another room, Mr. Bell would ask the audience for a word or strange noise then write it in Visible Speech. Aleck would return and reproduce the sound from the writing alone. Voila.

As a child growing up like this, he played at inventing machines that could talk and telegraphs that could listen. But he found his career in tutoring the deaf — by teaching them to pronounce the phonemes of Visible Speech, he eventually succeeded in teaching them to talk and read lips.

One of his students was Mabel Hubbard, daughter of prominent Boston lawyer Gardiner Greene Hubbard. Son of a Massachusetts Supreme Court Justice, Hubbard established water and gas and trolley utilities for Cambridge, Mass. — some of the first in the nation. He also fervently lobbied Congress to replace Western Union’s monopoly on the telegraph with a new corporation, the US Postal Telegraph Company, that would contract with the government Post Office.

At the time, telegraph wires blanketed the skies of Boston, hanging in a dense web above the buildings. Many desperately wished for someone to develop a telegraph that could send multiple messages over the same wire, so that many wires could be replaced with just one. The theory was that if one could transmit the messages using different tones, they would “harmonize” instead of interfere, leading the idea to be called the “harmonic telegraph”. Naturally, Alexander Graham Bell turned his tinkering to this problem and persuaded Hubbard (as well as Thomas Sanders, another father of a Bell student) to finance his research in exchange for a share of any future US profits. Further complicating matters, Bell had fallen in love with his student, Mabel Hubbard. Mr. Hubbard made it clear he did not approve of such a marriage unless Bell made a profitable discovery.

But Bell was simply a hobbyist, the real research was being done by a man named Elisha Gray. Gray ran Western Electric, the leading supplier of technical expertise to telegraph monopoly Western Union. From his lab in Highland Park, Illinois, he and his assistants worked feverishly at new discoveries. Bell was well aware of this and considered himself to be in a race with Gray to invent the harmonic telegraph first.

In 1875, Bell made a breakthrough in his work on the harmonic telegraph. But he was a crafty fellow — his deal with Gardiner and Sanders was only about splitting US profits; it said nothing about profits overseas. British law at the time granted patents only to inventions not patented elsewhere first, so Bell drew up several copies of his harmonic telegraph patent and sent some to be filed in Britain first. The rest were sent to DC to be filed as soon as word got back from Britain.

On February 14, 1876, while the lawyers were waiting in DC to file Bell’s patent, Gray filed a patent of his own. Bell’s lawyers were close to the patent officers and had asked to be tipped off if Gray tried to file something, so they could file Bell’s patent first. When Gray’s patent was placed in the patent office’s inbox, Bell’s lawyers hand-delivered Bell’s patent to the examiner, so they could claim he’d received Bell’s first.

The patent examiner, Zenas Fisk Wilber, had fought in the civil war with Bell’s attorney, Marcellus Bailey. Wilber was an alcoholic and owed Bailey money (a serious Patent Office ethics violation). To pay his friend back, he showed him Gray’s application. Bailey was startled to find it wasn’t a patent on a harmonic telegraph at all — it was a patent for a telephone, capable of transmitting all the sounds of human speech and music. He called for Bell to come to DC at once.

Bell did, and examiner Wilber showed him Gray’s patent as well, taking time to explain how it worked. Bell thanked him and returned that afternoon with $100 for his trouble. Bell then quickly scribbled an addition to his patent in the margin, adding that it should also cover “transmitting vocal or other sounds telegraphically” (this addition does not appear in any of the other copies).

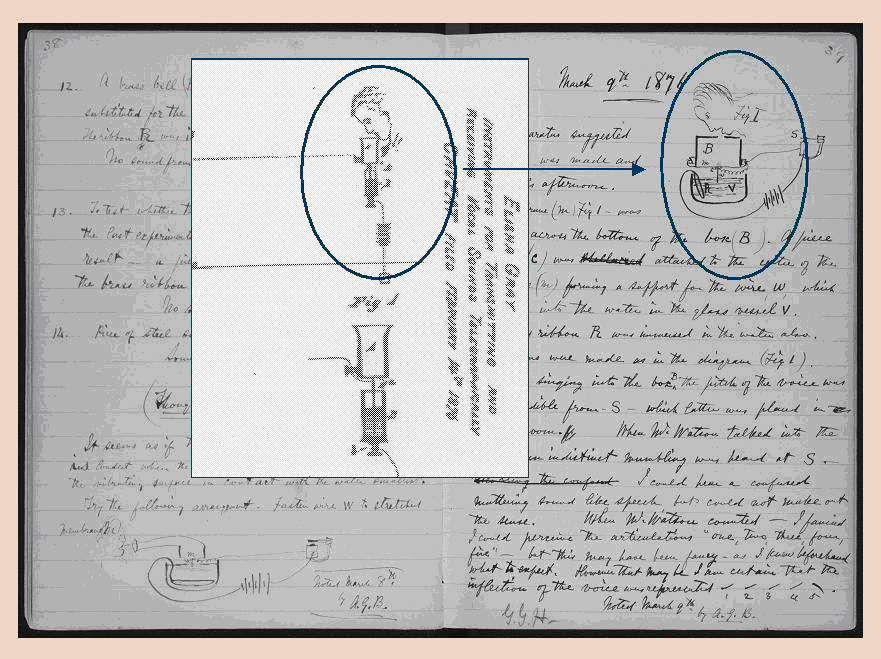

Contravening much standard practice at the time, Bell’s (modified) patent was quickly granted, while Gray’s was denied. It was issued the same day Bell returned home from DC, March 7, 1876. The following day, Bell drew in his lab notebook a copy of the diagram he had seen in Elisha Gray’s patent:

It took Bell several days of tinkering, but soon he was able to replicate Gray’s device. On March 10, he made that now-famous call: “Watson — come here — I want to see you.” Both Bell and his assistant Watson recorded the event that night in their notebooks.

But Bell didn’t want to simply duplicate Gray’s work; he wanted to invent a telephone of his own. He spent many months trying to develop a telephone that worked on a different principle, but never succeeded in getting it to clearly transmit audible speech. Bell was always extraordinarily reluctant to demonstrate his telephone, for fear that Gray would learn it was a simple copy. Mabel had to trick him into attending the Centennial Exposition, where he was supposed to demonstrate his work to a group of engineers, including Elisha Gray. On one occasion, Bell’s telephone patent was set to be annulled unless Bell would swear under oath that the invention was truly his. Bell fled the country, testifying only at the last minute after desperate pleading from Mabel.

The legal conniving a success, Bell and Mabel were soon married. Feeling guilty, Bell gave all but ten of his shares in the Bell Telephone Company to her and swore to never work in telephony again. The company was operated by Gardiner and others while Bell went back to working with the deaf. He always said he was more proud of his work for the deaf than of the telephone.

It took Gray a long time to realize that Bell’s patent was a fraud. For one thing, he was still focused on the harmonic telegraph; his customers at Western Union couldn’t imagine running telephone wires to every house and thus couldn’t see how talking over wires was particularly useful. For another, it took years for the story to leak out, through numerous court battles and Congressional hearings. Zenas Fisk Wilber’s affidavit confessing to what he’d done did not appear until 1886, a decade later. Bell’s notebooks, making clear the blatant copy, were not made public until the 1990s.

Bell’s biographers have gone to heroic lengths to explain away all the evidence. Refusing credit for the telephone just showed Bell’s humility; not being involved in the corporation showed his dedication to pure research. The fact that both patents were filed on the same day is a grand historic coincidence — or perhaps Gray stole the idea from Bell.

As a result, Gray is forgotten and Bell is remembered as one of history’s great inventors — not as he should be: a hobbyist and a fraud, forced by love into stealing one of the greatest inventions of all time.

Now playing: Regina Spector - “On The Radio”

You should follow me on twitter here.

January 5, 2009

Comments

Interesting story, but Phillip Reis was the one who invented the Telephone first - and Bell saw it, and copied some of his work.

posted by Pete on January 6, 2009 #

Interesting story here , unfortunately its not an isolated case , few year back i read a similar article written by Gladwel about Philio Fransworth , unsung inventor of Television . you can see same story with Nichola Tesla . more recently gary killdall was the REAL guy behind DOS but Bill G exploited it .

such cases makes me wonder is their a correlation between invention a technology and providing wide scale commercial acceptance of technology . is inventor ALWAYS right guy to do that ?

i am NOT AT ALL saying that there shouldn’t be attribution /accredition of inventor’s work or they shouldn’t be rewarded financially but when we see a lot many such example we need to think if our perception of end to end ownership ( invention to commercialization ) of a new tech needs a revision . Gladwells article is here http://gladwell.com/2002/2002_05_27_a_televisionary.htm

posted by Prashant Singh on January 11, 2009 #

@Prashant Fransworth invented the first fully electric TV, it was Baird who invented the first working TV (albeit electro-mechanical). Gladwell’s article is incorrect on this. And I don’t think BillG ever claimed he “invented” DOS; it’s common knowledge that MS purchased Paterson’s QDOS, and that was only developed because SCP didn’t know when CP/M was going to be ported to the 8086. Besides, IBM went to DRI first and MS second.

posted by Keith Gaughan on January 29, 2009 #

I find it funny that Bell is well known for the invention of the telephone after all the research I have done on it. Ever since i was probably about eight years old I have always been under the impression that Alexander Graham Bell was in fact responsible for this new technology. I’m currently 16 years old and find this article to be an eye opener for people/kids who are in my same position. Now after doing my research I have found that Bell didn’t even finish the invention. He was only able to come up with the receiver and couldn’t produce a microphone with the abilities to clearly produce sounds that were equivalent to the human voice. I knew that Gray had also invented the telephone but, I had no idea that theories like this are going around. It sounds like a pretty credible story and quite frankly I wouldnt be surprised at all if it was 100% true seeing as though Bell couldn’t even finish his invention. I picked this subject for my research paper because I thought it would be a challenging subject to write so much on but evidently now I’m able to come up with a 20 page story about not the history of the telephone but the controversy of the telephone.

posted by Casey Bouton on March 9, 2009 #

You can also send comments by email.